80 years ago today, my mother Edith Grosman, may her memory be a blessing, was packing her allotted 20kg and getting ready to board a foul, crammed tight cattle car that took her into the very bowels of hell: Hitler's human slaughterhouse and incinerator called Auschwitz Birkenau. Against astronomically tiny odds, she survived. She married my father shortly after the war and, unlike many of their Jewish survivor friends, mom and dad decided to stay in Prague. And it was in Prague that I was born, exactly 69 years ago today: March 3, 1953, which happened to be one of the coldest days of that year, with a low of -17 degrees Celsius. It also happened to be the last two days of Stalin’s terror - the tyrant died on March 5th that year.

Despite having been born during the darkest days of Stalinism, my Prague childhood was fabulous. I grew up surrounded by a now extinct breed of very special people: Jewish writers, doctors, philosophers, linguists...intellectuals who had survived Hitler, yet had retained grit and humor, honesty and a drive to succeed, as if to show the world: “you wanted to kill us but screw you bastards! We will start new families and new and fulfilling lives despite your Nazism, your Communism, your anti-Semitism” I grew up surrounded by books, long nights of impassionate debates, reminiscences of life before the war, racy jokes, rivers of Turkish coffee and a permanent haze of cheap cigarette smoke.

My childhood was rudely interrupted by the combined forces of Warsaw Pact armies - whatever Ukrainian teenagers are experiencing in March 2022, I experienced in August of 1968 when Russian tanks rumbled on the cobble stone streets of Prague.

My parents had stayed put after Hitler and Stalin, but the invasion was one bridge too far for them. We packed up and fled, leaving behind our city apartment, our little cottage in the woods, thousands of books and manuscripts and our black curly dog Peggy, who was left in the loving care of our neighbors but who nevertheless occasionally peeked out the window, looking for the little Fiat 60 my father drove, for the rest of her days.

Subsequently, I lived in Tel Aviv, Israel, where we trembled through the awful first few days of the Yom Kippur war. I served in the IDF, dated many beautiful Israeli women, none more beautiful than my fiancé Dina, whose brother was killed in a fierce tank battle in the Sinai desert in October 1973. Dina was never the same again after her brother's death and we drifted apart. Our split started a downward spiral of anxiety and depression for me. The separation, the war and subsequent loneliness - the feeling of an unstoppable flux with which one must do battle alone - that has stayed with me all my life. Dina and I reconnected and became good long distance friends. She now lives a content and quiet life in a village at the foot of the Himalayas.

Everything is always in a state of drift. None of the Jewish intellectuals of Prague, the world-weary beautiful souls, so full of pain and joy, are around anymore. I have two beautiful daughters, one a writer and journalist in Toronto and the other a nurse and internet entrepreneur in Kelowna, BC. I have a 16-year old grandson, a true-blue golf champion, who lives in Reykjavik, and two toddler grandkids in British Columbia. My dad, Ladislav Grosman, God bless his tender loving soul, passed away just short of his 60th birthday, in January 1981. He had achieved fame (if not fortune) and is today considered one of Slovakia’s celebrated native sons. The country of Slovakia bestowed the great honor on him by issuing a stamp with his image last year, the 100th anniversary of his birth. My mother, the last Mohican of the Prague circle, passed away at 96 less than two years ago.

I have played concerts and jazz festivals in Toronto, fishing villages in Iceland and lounges in London. I have taught English to wide-eyed young secretaries in Iceland and music to countless people across the world. I've had the privilege of sharing the state with on of the world’s finest jazz guitarists, the late, great Larry Coryell.

My first wife lives in her native Iceland, my second wife is a psychotherapist in Canada. And my third, and by far the best wife, my love, my shield, my tower of strength and the finest chef you could ever wish for, my Diane, lives with me in the small town of Winter Haven, Florida, where we have both somehow drifted after a life of struggle, conflict, strife, pain, happiness, mirth and disappointment...everything and anything life can serve up, we have embraced it.

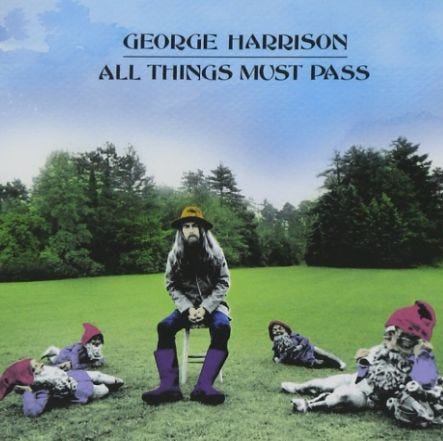

ALL THINGS MUST PASS

The armies are long gone from the streets of Prague but I will be a refugee as long as I live. Once you start running, you're on the run forever. It's had enormous benefits - I've seen places and met people I never would have met otherwise. But the price is heavy. That floating feeling of uncertainty, of uprootedness, remains day and night. You learn to live with it the way people learn to live with chronic conditions.

I continue to write words and music. Writing is therapeutic. One way or another we all look for ways to come to terms with the drifting, dreamy, shifting unsteadiness, that which Milan Kundera called "the unbearable lightness of being". Dust to dust, ashes to ashes, but between the dust and the ashes, during the crack of light between the two eternities of darkness, you do all you can to fill your life with joy, purpose, family and meaning.

Or as the Old Norse epic poem “Havamal” says: "livestock dies, kinsmen die, you yourself will die, but a good name dies never" And since I lived in Iceland, among many other places, for those interested, here’s the original Old Norse:

Deyr fé, deyja frændr,

deyr sjalfr it sama,

en orðstírr deyr aldregi

And finally, When musician Warren Zevon was dying, he was asked for his best advice for living a satisfying life. His reply: "Enjoy every sandwich"

69 years on this planet. I've loved a lot, hated some, and have learned a ton, though mostly just one fundamental thing:

ALL THINGS MUST PASS

This brought me to tears. Beginning with “ intellectuals who had survived Hitler, yet had retained grit and humor, honesty and a drive to succeed, as if to show the world: “you wanted to kill us but screw you bastards! We will start new families and new and fulfilling lives despite your Nazism, your Communism, your anti-Semitism” and through to the end.

My husband fled communist Yugoslavia. It is unbelievable how little history has taught us. You are correct, though, we have to get accustomed to the drift. The only constant is change.

Dearest George, you have a gift, this essay is beautifully written!